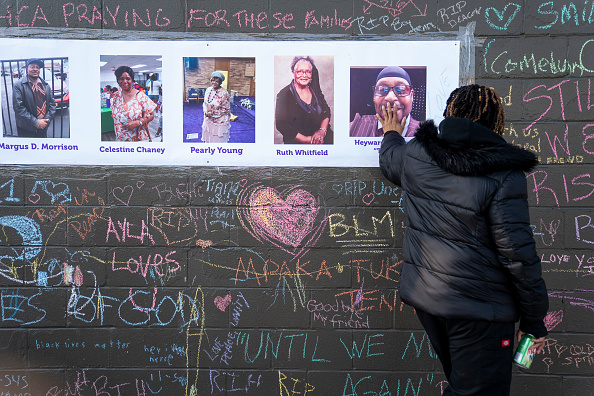

Featured Image Description: A memorial honoring victims of the TOPS supermarket shooting in Buffalo, New York, serves as a poignant reminder of community resilience and collective mourning. (Photograph by Kent Nishimura/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

Now we need to make sure we have sustainable aid, ongoing. So we had to not only be boots on the ground, but also put on suits and go into boardrooms to tell stakeholders: This crisis isn’t over just because the headlines moved on. – Stephanie Simeon, executive director Heart of the City Neighborhoods

In this episode we hear from Heart of the City Neighborhoods, a Buffalo-based nonprofit responding to the tragic mass shooting at Tops Friendly Market. Executive Director Stephanie J. Simeon shares how her organization, supported by Convergence Partnership alongside other local nonprofits, mobilized mutual aid to provide essential resources, create healing spaces, and support community resilience in the wake of white supremacist violence.

The episode explores the deep historical and cultural significance of Buffalo’s East Side, a neighborhood shaped by the Great Migration and home to generations of Black families. Simeon reflects on the trauma, the systemic conditions that made the community vulnerable, and the power of grassroots organizing in moments of crisis.

This podcast series serves as a final grant report for Convergence Partnership’s most recent grantee cohort. Through the voices of our grantees and their partners, we explore how civic narrative, mutual aid, and economic power shape the fight for racial justice and health equity.